Previous Article Next Article

Note: To search for something specific use the CS Museum search box to the left.

June 13, 1996

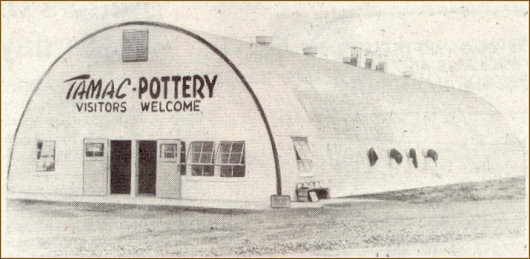

Neat Quonset Building, a style utilized by the military in World War II, housed Perry's Tamac Pottery plant when the business expanded in 1949. The 40' x 120' building is now the home of Corky Oden's painting and sandblasting business. (Photo copyright Oklahoma Publishing Co. Used with permission.)

Tamac Pottery was a promising young Perry industry for several years after World War II. It originated here, then disappeared and now it is a collector's item. How it began, what happened to it and the fate of some of the unique pieces that survive provide all the elements of an interesting story. Here's the first installment:

When the war ended in 1945, thousands of discharged veterans returned home and were added to the nation's unemployment rolls. They had trouble finding jobs. At the same time, small towns like Perry, which had been historically agriculturally centered, were looking for new industries to broaden their economic base. Veterans needed jobs and towns needed industries to put them to work. Into that scenario, two young veterans and their wives arrived here with a dream.

Leonard Tate, son of Henry and Zoma Tate, grew up in Perry and graduated from the Oklahoma A.&M. College school of business in 1942. His parents operated the Annex movie theater on the east side of the square and his grandfather had been owner-operator of the fabled Grand Opera House in that same location. Leonard had planned to have his own business but the war put that on hold. He joined the Navy and received a commission, served valiantly in the China-Burma-India theater and wound up recuperating in a New York hospital in 1945. There he met Marjorie Hemke and in September 1946 she became his wife.

Marjorie was born in Annapolis, MD, and grew up in the East. An art major, she graduated from Brown University in Rhode Island. During the war she was a drafter for General Electric and a designer of floor coverings for Congoleum-Nairn. There she became friends with Betty Macaulay. Betty's husband, Allen, was released from the Army in 1945. The Macaulays were natives of New Jersey. While they were still in New York, Leonard, Marjorie and the Macaulays became not only good friends but also partners in pottery-making. The decision to start a pottery plant was made because the men could not find jobs.

They chose Perry, Oklahoma, as a site because the city had a standing offer of free factory sites; some of the cheapest natural gas rates were available here; valuable technical assistance was just 24 miles away at Oklahoma A.&M.and they believed the Southwest offered the greatest opportunity for industrial expansion. This community welcomed them with open arms. The GI Bill of Rights also helped out. Its provisions for small businesses enabled Tamac to weather some early financial troubles.

The plant began as a modest addition built onto the side of Henry Tate's backyard garage at 920 Cedar street, where he stored fishing boats and related gear. Leonard and Allen constructed the addition and furnished it with equipment, including firing ovens, in the summer of 1946. Marjorie and Betty were integral parts of the operation from the beginning. Henry and Zoma pitched in as needed during the start-up phase and beyond. It was a family business.

The idea of a pottery plant was discussed by the two couples long before the Macaulays visited Perry. Marjorie had studied sculpture, modeling and design; Betty had taken a course in ceramics; Allen was a good mechanic; and Leonard had a good business education. It seemed that their combined talents could make a go of it.

After the addition to Mr. Tate's garage was finished, Leonard and his parents met Marjorie and her family in New Orleans. There they were married by her grandfather, a minister. The young couple came to Perry after their honeymoon and Betty joined the group that fall. Tamac formally became incorporated, company stock was sold, and they were on their way.

Work schedules at the new pottery plant typically involved 12 to 14 hours per day for the two young couples. Zoma Tate helped regularly in the retail store and Henry worked part time where needed. Soon they began producing a set of dishes, known as "One-Handers," for use in backyard barbecues, a fad which they correctly predicted would become popular throughout the U.S. Each set consisted of a 9-inch free-form dinner plate and saucer cast in one piece, with a corner built up in three grooves to hold silverware; a large cup and a tumbler. The sets got their name because all of the pieces could be easily balanced with only one hand. The cup had a tunnel to fit the index finger and thus insure a tight grip.

Macaulay is credited with the basic idea of the One Hander, and it was the company's best known product. However, he was not the creative partner; mechanics were his forte. He was inventive in improvising equipment and tools for the production line. But Marjorie's background in art and industrial design played a big part in creating the Tamac look.

Starting with butterscotch, a yellow color trimmed in brown, the owners soon added a yellow-green trimmed in darker green (avocado), a pine green with a frosted white trim (frosty pine), a brown with lighter trim (frosty fudge), and eventually a pink with lacy trim (raspberry). An ivory-beige combination was added by different owners in later years.

The outlook appeared bright. Long hours and hard work seemed to be paying off and the company saw the need to expand. Tamac's rise, and then the demise, will be described in the next Northwest Corner.