Previous Article Next Article

Note: To search for something specific use the CS Museum search box to the left.

June 15, 1996

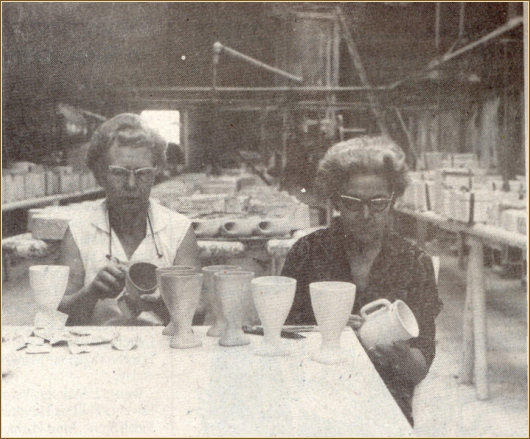

Careful Handwork added to the quality of products coming from Tamac Pottery plant some 40 years ago in Perry. Shown here are Doris Poe (left) and Mary Hladik, two employees of the firm at that time, lightly sanding surfaces of cups and goblets before the final glaze was applied. Mrs. Hladik and her husband, Joe, later purchased the Tamac business before it was finally closed some 25 years ago.

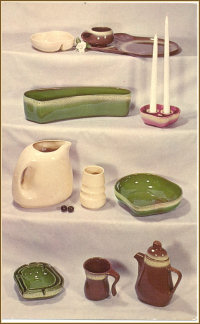

Examples of Tamac Pottery are shown in this photo, made from an advertising piece used by the Perry business at the height of the line's popularity. Collectors still avidly hunt these Perry-made items.

Tamac Pottery started in Perry in 1946 as a post-World War II dream of two young couples, Leonard and Marjorie Tate and Allen and Betty Macaulay. Marjorie and Betty met during wartime while working in the East. Leonard and Allen became acquainted after their separation from the Navy and the Army, respectively. They all wound up in Perry, Leonard's hometown, manufacturing the novel, free-form backyard barbecue dinnerware which bore a combination of their last names, Tamac. The line was well received from the day it was first offered.

Business was doing so well by 1948 that the owners were faced with an urgent need to expand. Perry's standing offer of free factory sites was accepted and the owners received an excellent 300-foot location at the southwest edge of Perry fronting on U. S. 64-77. The $30,000 building program was started in April. Stock was re-issued, money was borrowed from friends and relatives, and construction of a 40' x 120' quonset building was ordered. New equipment was installed to increase production. In September 1948 the plant was moved from the original backyard location at the home of Leonard's parents, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Tate, to the new site.

Marketing on a grand scale was a problem. Production was not. Local people could be trained to fire the kiln and process the raw clay into finished, attractive pieces of pottery. The work crew included about ten men and women most of the time. Teamwork made it possible to turn out around 300 hand-made pieces per day. Major national magazines took note of the unique "One-Hander" dinnerware, drop-in traffic increased at the local retail store, and sales quickly mounted. Some major department stores in Oklahoma, Texas and elsewhere in the Southwest stocked Tamac Pottery. One of the major accounts was Garfinkle's Department Store in the nation's capital.

Leonard and Allen both felt the chain of events which led to establishment of the venture was more than a coincidence. "When two plain citizens with little pull, and few contacts, can secure materials where there are none, get help or advice when none was anticipated, and, finally, hit on a successful idea the first try, it is inevitable that we should conclude that the hand of God is pulling strings somewhere," they were quoted as saying in a 1948 interview.

But the young industry was under great pressure to expand its output, its product line and the number of outlets. Qualified sales representatives were hard to find. In the larger stores, Tamac suffered an identity crisis and often became lost in the shuffle among other brands.

By 1950 Allen and Betty had lost their zeal for pottery making. They decided to leave, so Leonard and Marjorie bought their interest in the company and the Macaulays returned to their roots in New Jersey.

Public acceptance of Tamac was never a problem. Customers liked the colors, the variety, the quality and the availability of the Perry-made product, but distribution and marketing were something else. Financial problems mounted, and by 1952 the company was forced into bankruptcy. Leonard's uncle and aunt, Mr. and Mrs. Earl Bechtold, bought the business and their son, Raymond, operated it successfully for a few years. He added several pieces to the line, but in a few years he also ran into financial difficulties and Tamac again was sold to Joe and Mary Hladik. Their daughter, Lenita Moore, and Mrs. Hladik operated it for a few more years, but in the 1970s Tamac was closed forever.

Leonard and Marjorie moved back East after leaving the business. Leonard was a sales representative for Arrow Shirt Co. for a time, then obtained a government position in he Washington, D. C. The Tates lived there and abroad until moving to Winchester, VA, in 1969. Leonard died in 1987. Marjorie still makes hex home in Winchester and pursues her interests in painting and arts club work. A daughter, Vicki, and husband, John Knauss, live nearby. Vicki was Perry's New Year's Baby when she was born here on Jan. 1, 1952. The Tates' other daughter, Alice, lives in Florida.

The Tamac quonset building now houses Corky Oden's painting and sandblasting business on the curve of U. S. 64-77 at the south edge of town. Tamac was the subject of numerous articles in journals of general circulation during its heyday, and it continues to interest collectors today. Many samples of the One-Hander and other articles turned out by the Perry pottery plant are now on display in shops specializing in collectibles, such as Carol Steichen's Antiques on the Square and Roy Kendrick's Cherokee Strip Antique Mall, both on the north side of the square. Frankoma and Other Oklahoma Potteries, by Phyllis and Tom Bess, gives a brief but interesting account of the Tamac story.

Tamac's forward-looking design, conceived nearly 50 dears ago, is still considered significant by today's artisans. The Dallas Museum of Art recently featured an exhibit on Hot Cars, High Fashion, Cool Stuff. Designs of the 20th Century. The objective was to tell the history of design in the 20th century through decorative and fine arts using pieces on loan as well as from the museum's own collection. Among the latter were several examples of Tamac pottery. Other pieces shown included a Ferrari, a vintage Rolls Royce, Dior and Coco Chanel fashions, art deco work by Erte, and pieces by Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. Pretty heady company for the Perry--made pottery. Interesting to note, there were no pieces from Frankoma.

But the color, the drama, the heartbreak and the achievement of the onetime Perry business cannot be fully told in mere words and cold pieces of pottery. It was a stirring adventure, a heady climb to the top of the highest part of the amusement park's roller-coaster thrill ride, then the fast descent into oblivion, all combined with unadorned human pathos, romance and frustration. Those pieces of Tamac Pottery are made of more than just clay. They contain the elements of a classic American success story that somehow fell short.